GameEngineBook

Table of Contents

- Chapter 7: Python Scripting

- Why Script When You Can Logic Brick It?

- So What Exactly Is Python?

- Where to Learn Python

- Python and the Game Engine

- Integrating Python in the Game Engine

- Writing Your Python Scripts

- Designing Your Python Script - Study Example

- Using the Game Engine API - Application Programming Interface

Chapter 7: Python Scripting

Congratulations, you finally arrived at one of the most technical parts of the book. Keep that in mind in case you get lost.

The Blender game engine was once famous for letting you create a full game without touching a single piece of code. Although this may sound attractive, it also leads to a very limited game-making experience. Logic bricks, as presented in Chapter 3, are very handy for quick prototyping. However, once you need to access advanced resources, external libraries and devices, or simply optimize your application, a programming language becomes your new best friend.

Through the use of a scripting language called Python, the game engine (as Blender itself) is fully extensible. This programming language is easy to learn, although extremely powerful. Be aware, though, that you will not find a complete guide to learning Python here. There are plenty of resources online and offline that will serve you better. However, even if you are not inclined to study Python deeply now, sooner or later you will find yourself struggling with script files. So, it’s important to know what you are dealing with.

Yes, You Can

For those experienced Python programmers (or for those catching up with the reference learning material), always remember: if you can do something with Python, chances are, you can do it in the game engine.

After the brief overview in the Python basics, we will explain how to apply your knowledge of Python inside the game engine. You’ll also learn how to access the Python methods, properties, and objects you’ll be using.

Why Script When You Can Logic Brick It?

We can compare logic bricks with real bricks. On the one hand, we have strong elements on which to build our system, but, on the other hand, we have a system as flexible as a blind wall.

There are many occasions when the same effect can be achieved in different ways. Different phases of the production may also require varied workflows. The reason for picking a particular method is often personal. Nevertheless, we present here a few arguments that may convince you to crack a good Python book and start learning more about it:

-

Sane replacement for large-scale logic-bricked objects.

-

Better handling of multiple objects.

-

Access to Blender’s advanced features.

-

Use features that are not part of Blender.

-

Keep track of your changes with a version control system.

-

Debug your game while it runs.

Logic Brick, the Necessary Good

You can’t ever get away from logic bricks. Even when using Python exclusively for your game, you will need to invoke the scripts from a Python controller. The ideal is to find the balance that fits your project.

Sane Replacement for Large-Scale Logic-Bricked Objects

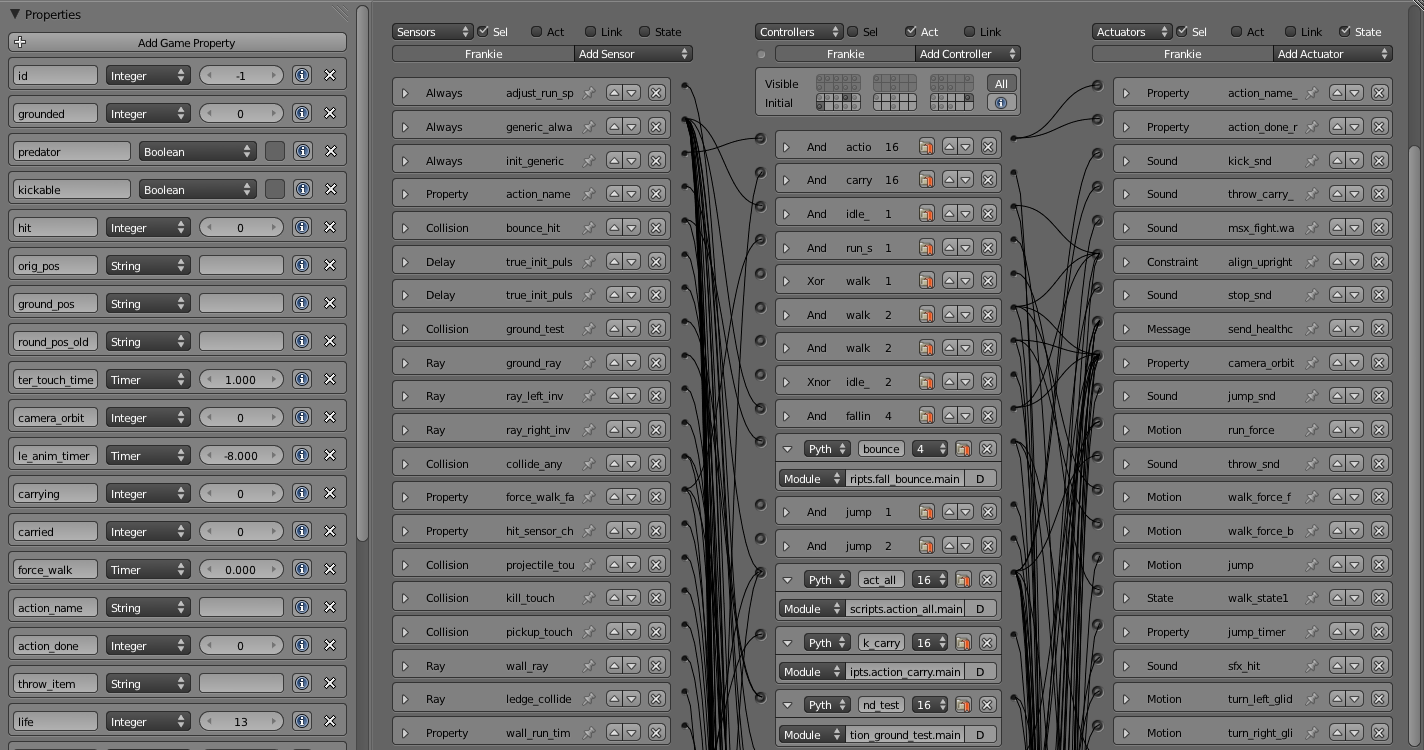

It’s always good to have an excuse to show an image in a programming chapter, and here it is. In Figure 7.1 you see the logic bricks for Frankie, the main character of the open game Yo Frankie!

This system is well organized: different actions belong to different states and sensors; controllers and actuators are properly named. Nevertheless, it’s not hard to lose yourself trying to understand which sensor connects to which controller. One of the reasons for such a complex project to rely on logic bricks is because Yo Frankie! serves as a didactic project for artists wanting to start with the game engine. Anyone with a little programming experience can take the files and expand the game freely. (Have you tried it yet?)

However, you often aim for performance and workflow. Having everything centralized in a single script file can save you a lot of time.

Another important aspect while working is to document your project. It’s easy to open a file only a few months old and find yourself completely lost. Script files, on the other hand, are naturally structured to be self-documented. To document logic bricks, you need to rely on text files inside or outside your Blender files (and neat image diagrams). It’s definitively not as handy as inline comments along your code. (Code diagrams can still be useful, but that’s a different topic.)

For the Artist Behind the Programmer Façade

Please resist to the temptation to create ASCII art while documenting your scripts.

\_\_\_\_\_.-.\_\_\_\_\_

'-------------'

| | /

| | \_\_/

\ /

| |

\ /

| >|< |

\\_\_\_\_\_\_\_/

.'==========='.

/ o o o o o o o \

'-----------------'

Better Handling of Multiple Objects

Big projects lead to multiple files[md]this is an inevitable truth. Even when you use external linking and libraries, it’s crucial to optimize the time spent in changing multiple sets at once. This is one of the weaknesses of logic bricks[md]they make it hard to automatically change a big range of elements at the same time.

If you need to change a property name or initial value of an object, you will need to repeat that change in other instances of the same. We have ways to make it easier by using copy and paste of logic bricks/properties between objects or even through logic sharing. Nevertheless, you will still have to update all the Property sensors, controllers, and actuators that may rely on the old value. That’s especially true for objects with logic bricks across them[md]as we saw, the game engine allows you to link logic bricks from different objects. However, self-contained objects/logic bricks are easier to work with (and with less spaghetti ).

If you thought that Figure 7.1 was a mess, try to make sense of Figure 7.2. Here we have the logic bricks of Frankie, plus the objects that have logic bricks connected to it. As you recall, you can restrict the visible logics through the Show Panel option, but this illustrates how difficult it is to get a global view of your system.

Once you start to work with scripts, you will see how easy it is to assume control over all your scene elements in a global way. It will give you lots of benefits in the long run.

Access to Blender’s Advanced Features

You will be happy to know that the game engine has a powerful set of features beyond those found in the logic brick’s interface. Also, almost all the functionality found in the logic bricks can be accomplished through an equivalent method of the game engine API (which will be covered in the section “Using the Game Engine API - Application Programming Interface”). The API ranges from tasks that could be performed with logic bricks, such as to change a property in a sensor or to completely remove an object from the game, all the way to functionality not available otherwise, such as playing videos and network connection.

We Never Forget the First Patch

The ability to directly end an object from Python was introduced in Blender 2.47. This is a good example of how convenient script methods can be. And here comes a bit of history . . . back in August 2008, the project we were working on, OceanViz (read more about it in the Case Studies in Chapter 10), required a huge amount of objects to dynamically pop up and die. The game engine simulation had critical performance issues, and optimization was not a luxury there. At that point, we had reduced ending objects by having a simple Property sensor that would trigger an Edit Object EndObject actuator. So far, so good. However, one extra sensor running every frame for every single object in the scene was costing us some performance we could use elsewhere. (We are talking about hundreds of objects here.) When blaming our software didn’t help (it may eventually), it was time to get our hands dirty. After some hard work and some online help, we had our first patched version of Blender game engine working right in front of us. We didn’t need those multiple sensors anymore because a simple

myobjects.endObject()

was doing the job now. (Where is the champagne?) To be allowed to extend our own version of Blender in that way was cool. To submit the patch and have it implemented in the core of Blender was memorable.

There are a few reasons for not having all the methods accessible through logic bricks. First, a graphic interface is very limited for complex coding. You may end up with a slow system that is far from optimized. Second, having methods independent from the interface allows it to be expanded more easily and constantly (from a development point of view). Some advanced features, such as mirroring system, dynamic load of meshes, OpenGL calls, and custom constraints would hardly fit in the current Blender game engine interface. They would probably end up not being implemented because of the amount of extra work required. Other things you will find in the game engine built-in methods are: make screenshots; change world settings (gravity, logic tic rates); access the returned data from sensors (pressed keys, mouse position); change object properties (camera lens, light colors, object mass); and many others we will cover in the course of this chapter.

Use Features That Are Not Part of Blender

No man is an island. No game is an island either (except Monkey Island). And the easiest way to integrate your Blender game with the exterior world is with Python. If you want to use external devices to control the game input or to tie external applications to your game, you may find Python suitable for that task.

Here are some examples that showcase what can be done with Python external libraries:

-

Grab data off the Internet for game score.

-

Control your game with a Nintendo Wiimote controller.

-

Combine Head-tracking and immersive displays for augmented reality.

Those possibilities go with the previous statement that almost everything that you can do with Python, you can do in the game engine. And since Python can be used with modules written in other languages (properly wrapped), you can virtually use any application as a basis for your system.

Cross-Platform, Yes; Cross-Version, Not

To use external libraries, you must know the Python version they were built against. The Python library you are using must be compatible with the Python version that comes with your Blender. It’s also valuable to check how often the library is updated and if it will be maintained in the future.

Keep Track of Your Changes with a Version Control System

If you take a Blender file in two different moments of your production, you will have a hard time finding what has changed between them. This is because Blender’s native file format is a binary type. Binary files are written in a way that you can’t get to them directly[md]they are designed to be accessed by programs and not by human beings.

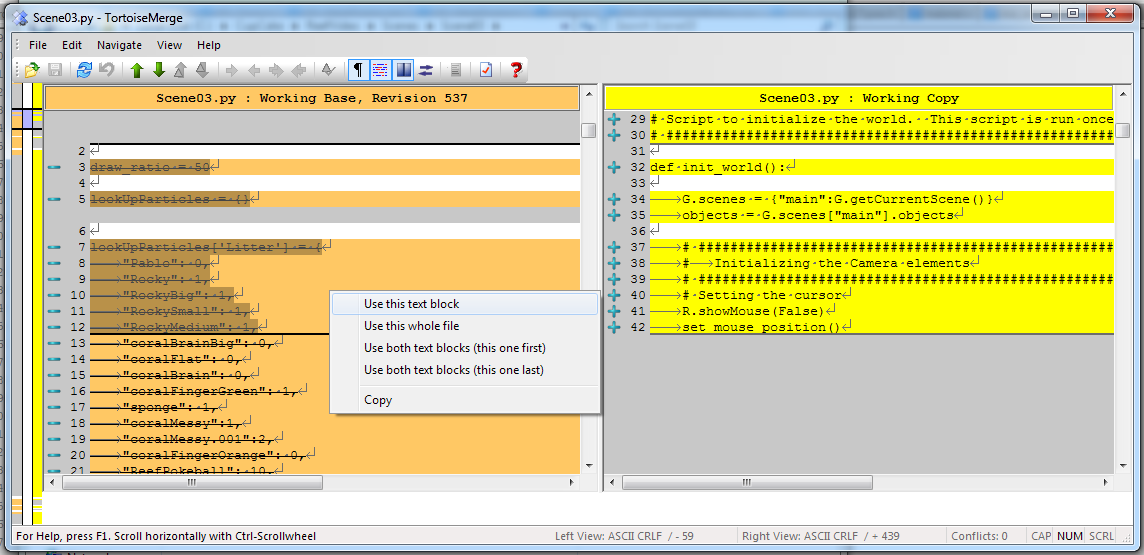

Scripts, on the other hand, are plain text files. You can open a script in any text editor and immediately see the differences between two similar files. Finding those differences are vital to going forward and backward with your experimentations during work. Actually, if you don’t want to check for differences manually, you may want to consider using external script files with a version control system such as Git, SVN, Mercury, or CVN.

And the Catch Is …

This works only for scripts maintained outside Blender. This is one of the strong reasons to prefer Python Module controllers as opposed to Python Script controllers.

A version control system allows you to move between working versions of your project files. It makes it relatively safe to experiment with different methods in a destructive way. In other words, it’s a system to protect you from yourself. In Figure 7.3, you can see an application of this. Someone changed the script file online while we were working locally on it. Instead of manually tracking down the differences, we could use a tool to merge both changes into a new file and commit it. We were using TortoiseSVN for Windows here, a graphic interface to use with a SVN system. For Linux systems, svn command-line plus the software “meld” work just as well.

Debug Your Game While It Runs

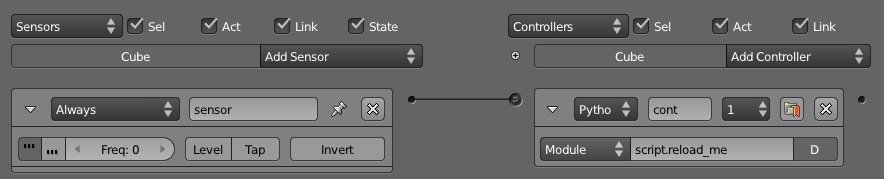

Interpreted languages (also known as scripting languages) are slower than compiled code. Therefore, to speed up their performance they are precompiled and cached the first time they run (when you launch your game). This is not mandatory, though, and if you are using external Python scripts (instead of those created inside Blender), you can use the debugging button to have them reloaded every time they are called.

In Figure 7.4, we have the scripts.reload_me module that will be reloaded every frame. That way you can dynamically change the content of your scripts, variables, and functions without having to restart the game. Try it yourself: copy the content of the folder \Book\Chapter7\1_reloadme to your computer and launch debug_python.blend. Play your game, and you will see a spinning cube. The speed of the cube is controlled by the 14th line of the file script.py, found in the same folder.

# edit the speed value and you will see the rotation changing

# (try with values from 0.01 to 0.05)

speed = 0.025

Without closing Blender or even stopping your game, open the file script.py in a text editor, change this line to 0.05, for example, and save it. You will see the speed changing immediately. Your game is literally being updated at runtime, and you can change any module that’s been called with the debug option on.

Turn It Off When You Leave

Remember to turn debugging off when you are done with this script. Reloading the script every frame can drastically reduce your performance.

So What Exactly Is Python?

Now that you are aware of all the benefits of using Python, it’s time to understand what Python is. Once again, we can’t go over all the aspects of the language here. Nevertheless, a general overview is still desirable to help you understand the examples presented in this book.

To study your scripts, you must be aware of the following aspects:

-

Flexible data types

-

Indentation

-

OOP[md]Object-Oriented Programming

Flexible Data Types

Whenever you write a program, you have to use variables to store changing values at runtime. Unlike languages such as C and Java, Python variables are very flexible: they can be declared on the fly when you first use them; you can assign different data types for the same variable; and you can even name them dynamically:

for i in range(10): exec("var\_%d = %d" % (i,i))

This snip of code is the equivalent to the following:

var_1 = 1

var_2 = 3

var_3 = 3

(...)

As you can see, the variable names are created at runtime. Therefore, if you name your objects correctly in the Blender file, you can store them in variables named after them. The following code snip assigns the scene objects (retrieved from the game engine) to variables named after their names.

(...)

for object in scene.objects:

exec("%s = \"object\" " % (object.name))

Although we have flexible data types, we must respect variable types while manipulating and passing/returning them to functions. Here you can see a list of the data types you will find in the Blender game engine API:

- Integer: This is the most common of the numerical types. It can store any number that fits in your computer memory. You can perform any regular math operations on it, such as sum, subtraction, division, modulus, and potency.

my_integer = 112358132134

- Float: This type is very similar to integers, but has a range of numbers that includes fractions. If you divide an even number by its half, Python will automatically convert your integer to a float number.

simple_float = 0.5

phi = (1 + math.sqrt(5)) / 2 # ~1.618

- Boolean: As simple as it sounds, this data type stores a true or a false value. It can also be understood as an integer with the value of 1 or 0.

i_am_enjoying_the_book = True

i_am_understanding_the_book = i_am_enjoying_the_book - 1

- List: A list contains a conjunct of elements ordered by ascending indexes. Although the size of a list can change on the fly, you can’t access a list index that wasn’t created yet (this will crash Python). List can have mixed elements such as integers, strings, and objects.

my_list = [3.14159265359, "PI", True]

- Tuple: This is another kind of list where elements can’t be overwritten. As with lists, you can read them using indexes. But it’s more common to access all the values at once, assigning them to different variables.

t,u,p,l,e = (1,2,3,4,5) # works as: t = 1, u = 2, p = 3, ...

- String: Whenever you need to store a text, you will use strings. As words are a combination of individual letters, a string consists of individual characters. Indeed, strings can be understood as a list of characters because you can access them using their location index, though you can’t overwrite them (like in a tuple).

python = "rulez"

- Dictionary: Like a list, a dictionary can store multiple values. Unlike a list, a dictionary is not based on numerical index access. Therefore, we have strings working as “keys” to store and retrieve the individual variables. In fact, anything can be a key to a dictionary, a number, an object, a class …

_3d_software = {"name ": "Blender", "version": 2.6}

- Custom Types: These are things such as vectors and matrixes. The game engine combines some of the basic data types to create more complex ones. They are mainly used for vectors and matrixes. That way you can interact mathematically with them in a way that basic types won’t do.

mathutils.Vector(1,0,0) * object.orientation # the result is a Matrix

Indentation

Indentation[md]the amount of white spaces or tabs you leave before a new line.

When coding in a particular programming language, it’s mandatory to follow its general syntax. In that regard, Python is one of the most restricted languages out there. Think of this as a tough grammar exam. You won’t be able to score high unless you follow all the pre-established grammar rules. Now imagine that it could be even worse[md]as bad as a written legal document. We are talking about strict paragraphs, indentation, information hierarchy, and similar rules.

As in a legal document, those rules have a raison d’etrê. With strict form/syntax, you can focus more on the content of the text. And ambiguity in the context of code making is fatal.

Indentation is the most important aspect of Python syntax. Python code uses the indentation level to define where loops, functions, and general nesting start/end. Take a look at this example:

1 def here_i_am(): # definition of the first function

2 print("I'm inside the first function.")

3 print("I'm outside the function.")

4 def but_I'm_not_here(): # definition of the second function

5 print("For you can't see me!")

6 print("I'm still outside the function.")

7 here_i_am() # calling the first function

Here we are defining a function (1–2), calling a built-in print function (3), defining another function (4–5), calling another built-in print function (6), and finally calling the first function we declared (7).

The output of such script will be:

I'm outside the function.

I'm still outside the function.

I'm inside the first function.

The first thing you may notice is that Python runs from top to bottom. Therefore, you must define your function before you call it. Secondly, you can see that the second function is never called. So how can the code interpreter determine which print statements to call? The answer is: indentation! Whenever you change the indentation level (lines 1–2, 2–3, 4–5, and 5–6), you determine the hierarchical relation between the elements. Therefore line 2 belongs to the function defined in line 1, line 5 to line 4, and the other lines are all at the same level.

Whether to use spaces or tabs in your scripts is a matter of personal preference. But be consistent[md]it makes it easier to copy and paste your code for reutilizing it.

Pound Sign, I (Finally) Love You

If, like me, you never understood the reason for the number/pound sign key (#) on your phone, you will eventually find it very useful. In Python, any text to the right of a pound sign is ignored by the interpreter. Therefore, the pound sign is used to add commentaries to your code or to temporarily deactivate part of it.

OOP - Object-Oriented Programming

Since games deal with 3D world objects, it makes sense to use a language that is oriented to them. The game engine itself is written in C++, a very strong and object-oriented language, and Python OOP capabilities let you handle the game data in a Python-native way. It reflects in the game engine objects having their own set of functions and variables directly accessed from a Python API (to be explained later in this chapter in the section “Using the Game Engine API - Application Programming Interface”).

In the Python code, you can (and will) create your own classes, modules, and elements. For example, you may want to control some 3D elements as a group defined by your code. It will make it easy to get to all of them at once. Therefore, you can have a custom class that will store all the related objects you want to access and preserve some properties as a group.

Open the book file: \Book\Chapter7\2_oop\oop.blend

The first script that runs in this file is the init_world.py. Here we are creating two groups to store different kind of elements (cube and sphere). In order to sort the objects between the groups, we go over the entire scene object list and check for objects with a property “cube” or “sphere” and append them to their respective lists.

# ############### #

# init\_world.py #

# ############### #

import bge

from bge import logic as G

from bge import render as R

# showing the mouse cursor

R.showMouse(True)

# storing the current scene in a variable

scene = G.getCurrentScene()

# define a class to store all group elements and the click object

class Group():

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.click = None

self.objects = []

# create new element groups

cube_group = Group("cubes")

sphere_group = Group("sphere")

# add all objects with an "ui" property to the created element

for obj in scene.objects:

if "cube" in obj:

cube_group.objects.append(obj)

elif "sphere" in obj:

sphere_group.objects.append(obj)

elif "click" in obj:

exec("%s\_group.click = obj" % (obj["click"]))

G.groups = {"cube":cube_group, "sphere":sphere_group}

After storing them in the global module bge.logic, we wait for the user to click in the cube or sphere in the middle of the scene. When that happens, it will toggle the value of the on/off property of the cube or sphere. The following script (which runs every frame) will then hide/unhide the group’s objects accordingly.

## ################## #

# visibility\_check.py #

# ################### #

from bge import logic

# defines a function to hide/turn visible all the objects passed as argument

def change_visibility(objects, on_off):

for obj in objects:

obj.visible = on_off

# retrieve the stored groups to local variables

cube_group = logic.groups["cube"]

sphere_group = logic.groups["sphere"]

# read the current value of the "on\_off" property in the cube/sphere

cube_visible = cube_group.click["on\_off"]

sphere_visible = sphere_group.click["on\_off"]

# calls the function into the group object with the visibility flag

change_visibility(cube_group.objects, cube_visible)

change_visibility(sphere_group.objects, sphere_visible)

And we are done with this interaction. Play with the file by adding new elements (tubes, planes, monkeys) and make them interact as we have here. A few copies and pastes should be enough to adapt this code to your new situation. Remember to note the current indentation used.

Where to Learn Python

If you have previous experience with another programming language, you will learn Python in no time. If you go over some basic Python tutorials, look at some script examples, and check the Blender game engine API, that might be enough. But if learning Python is your first step into coding experience, don’t worry. Take the time to read through the basics of the language, start with the simplest tasks, and never give up.

Usually, a good way to start is tweaking ready-to-use scripts, which doesn’t require you to understand all the aspects of the language before your first experiments. Also, it gives you a good motivational boost by producing quick results for your efforts. We recommend you first learn Python and then focus on its application in the game engine. But you may be more comfortable messing with game engine files first and then later learning Python more deeply.

Online Material

Below are some websites where you can learn more about Python.

www.python.org

Learn about new Python versions, API changes, and module documentation.

www.blender.org/documentation/blender_python_api_2_66_release/#game-engine-modules

Official BGE API Documentation[md]all the built-in modules that can be used with the game engine.

www.blenderartists.org/forum

Blender Artists forum[md]you can find good script examples in the Python section (general Blender Python) and in the Blender game engine section.

Dive Into Python 3 covers Python 3 and its differences from Python 2. A complete book available online.

Offline Material

Here are some other resources to help you learn Python.

Learning Python, by Mark Lutz and David Ascher, published by O’Reilly Media

You can learn Python in a week with this book. You can also find it as an e-book, which is useful for searching quickly. Try to get the newest edition of the book you can find. Different Python series (2.x, 3.x) have certain particularities you don’t want to have to deal with.

Before Buying a Book

If you are going to buy a Python book, be aware of its target audience. Some books are written for people with absolutely no previous knowledge in programming languages, while others assume otherwise. And make sure the book covers the Python version that is included in Blender (at the time of writing, Python 3.2).

Yo Frankie! DVD www.yofrankie.org

An open game made with the game engine by the Blender Foundation. You can download all the files of this project for free and go over their scripts. Although this can be confusing for someone in the first phases of learning Python, it’s good reference material for later on.

Python Built-in Help

You can also access help directly in Python.

dir(python_object)

The Python function “dir” creates a list with all the functions/modules/attributes available to be accessed from this object.

help(python_function)

This built-in function reveals the official documentation for this module or data type.

Python and the Game Engine

This whole chapter is organized into three main parts: why, what, and how. Thus, if you have read from the beginning, you already have solid reasons to start using scripts for your project, and you understand what Python is. The final part of this chapter will cover how to use your Python knowledge inside the game engine. This part is divided into four submodules:

-

Integrating Python in the game engine.

-

Writing your Python scripts.

-

Designing your script.

-

Using the Game Engine API.

Integrating Python in the Game Engine

In the game engine, the script interface is controller-centric by design. Therefore, you can consider the Python script simply as a more complex controller to replace the Expression or the Boolean controllers. In those cases, the script will be responsible for controlling how the sensors are related with the actuators of a given object. In fact, the sensors, actuators, and even the object where you are calling the script from are all attributes of the controller.

As we mentioned earlier, with a Python script you can control external devices, control multiple objects at once, and much more. However, you will never be free from using a logic brick framework. And from the combination of logic bricks, individual sensors, global sensors, and actuators, the elegance of your system will arise.

In the first example, you will find a very simple case study of how to make your Python controller work. It will cover the basic behavior of receiving sensors’ input in the script and triggering actuators from it.

Open the file \Book\Chapter7\3_template\abracadabra.blend.

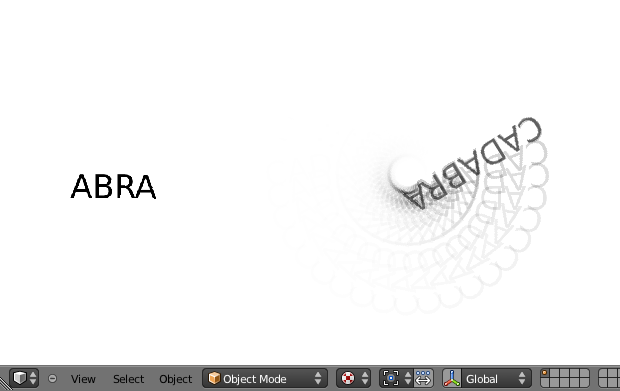

Launch the game and keep the spacebar pressed. In Figure 7.5, you can see the result before and after you press the key. Can you read the spinning text? It may not be impressive, but it certainly is didactic. Here is the script behind this effect:

import bge

from bge import logic

cont = logic.getCurrentController()

owner = cont.owner

scene = logic.getCurrentScene()

objects = scene.objects

text_obj = objects["Text"]

sens = cont.sensors['my\_sensor']

act = cont.actuators['my\_actuator']

if sens.positive:

cont.activate(act)

text_obj.text = "CADABRA"

else:

cont.deactivate(act)

text_obj.text = "ABRA"

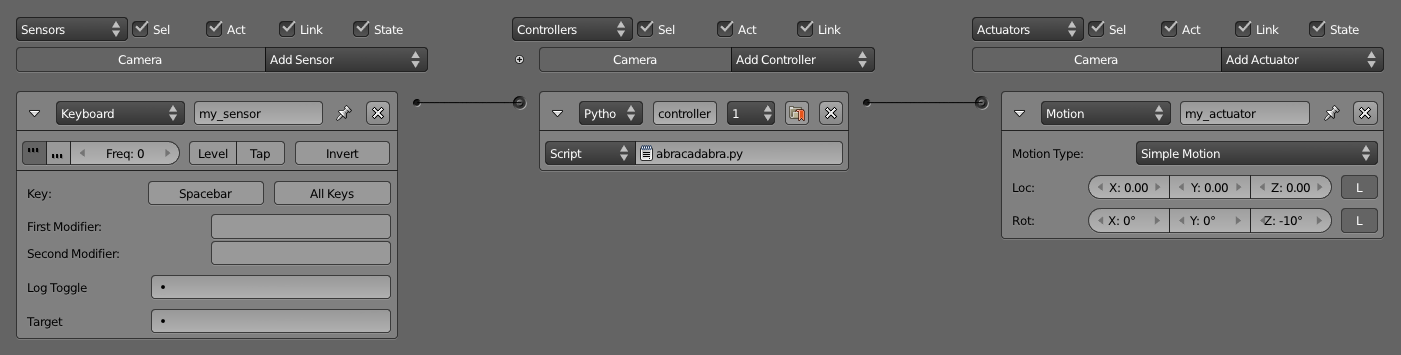

This script is triggered from a keyboard sensor, runs from a controller in the camera object, activates an actuator in the camera itself, and changes a property in the text object. Figure 7.6 shows logic bricks for this one.

Let’s look at it from the beginning:

import bge

from bge import logic

The first lines import the module bge and then the submodule logic. No big deal here. We actually don’t need to explicitly import the bge module since we are importing a submodule directly. However, it doesn’t hurt to do it. Lines 4 and 5 will store the current controller in a variable and create a pointer to the object where it was called from (known as owner). We are not using the owner variable here, but it’s good to be familiar with it. You will be using it a lot.

cont = logic.getCurrentController()

owner = cont.owner

The following lines get more elements from the game to be used in the script: scene will give you direct access to the current scene; objects is the current list to be used later; text_obj is one element of the objects list (accessed by its name in Blender).

scene = logic.getCurrentScene()

objects = scene.objects

text_obj = objects["Text"]

Remember when we said that the game engine is controller-centric? All the sensors and actuators are accessed from the controller, not from the object they belong to (its owner), as you might expect. Lines 11 and 12, respectively, read the built-in sensor and actuator list to get the ones we are looking for.

sens = cont.sensors['my\_sensor']

act = cont.actuators['my\_actuator']

In a way similar to how logic bricks work, we are going to activate the actuator if the sensor triggers positive and deactivate it otherwise. The deactivation happens in the frame after the sensor ceases to validate, for example, the key is unpressed or the mouse button is released.

if sens.positive:

cont.activate(act)

else:

cont.deactivate(act)

We are not restricted to controlling only actuators, though. Lines 15 and 18 change the text of the object when you press/release the spacebar:

15 text_obj.text = "CADABRA"

18 text_obj.text = "ABRA"

This file can be simple, but holds the essence of the game engine architecture design. Now is a good time to go over the three game engine template files that come with Blender. Go to Text Editor Templates GameLogic* and spend some time studying those examples. You can also get them on the book files under \Book\Chapter7\3_template.

Writing Your Python Scripts

If you haven’t started your own scripts, now is a good time to do so. You will need a text editor, the API modules documented, and a good way to test your files.

Text Editors

It’s important to find a script editor that you find pleasant to work with. The most important features you will be looking for are: syntax coloring and highlighting, auto indentation, and auto completion. You can find editors with even more features than these, so experiment with different alternatives and decide what’s best for you.

Notepad? Notepad++

Most of the scripts presented in this chapter were coded using Notepad++. This Windows-based open source text editor is not Python specific, but handles Python syntax highlighting well. You can download Notepad++ from their website: http://notepad-plus.sourceforge.net If you are using Linux or OSX, there are plenty of native alternatives that may serve you even better.

Blender Text Editor

As you probably know, Blender has its own internal text editor (see Figure 7.7). Although it may not be as powerful as software designed exclusively for this particular task, it can be very convenient. It’s useful for quick tests, small scripts, or when you want to keep everything bundled inside the Blender file. Here are its main features:

-

Syntax highlighting

-

Dynamic font sizes

-

Indentation conversion (spaces to tabs and vice versa)

-

Line counting and navigation

-

Search over multiple internal files

-

Sync with external files

Reference Material and Documentation

Since the game engine Python API is available online, you have an official excuse to keep a Web browser open while you work. It’s not a bad idea to keep an offline version of it, too. (You can find it on the book files.) Use it when you need to be more productive and the Internet is getting in your way (as in, always).

It’s good if you can start to gather example materials from the Internet and keep them organized. If you use the append feature in Blender to navigate to and import text files from your “collection,” you will not even need to open another Blender application. Also, if you are consistent with your naming style, indentation rules, and file structures, you will find easy to reuse your own scripts.

Testing Your Scripts

It doesn’t matter how easy Python is, you will spend evenings testing and retesting your scripts before you have them working properly. The more complete way to test your script is to play it inside the game engine. However, you may not want to load your game every time you need to be sure of some Python syntax, data types’ built-in functions, or simply to check if the math of a result is correct.

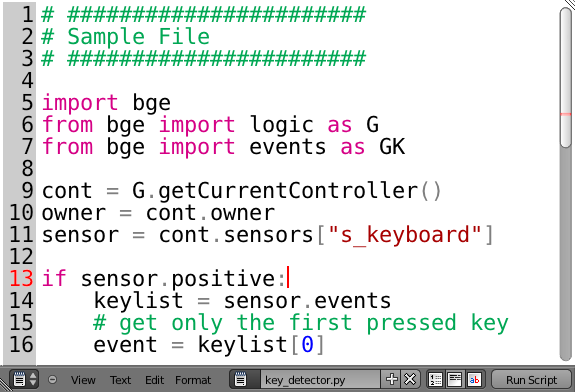

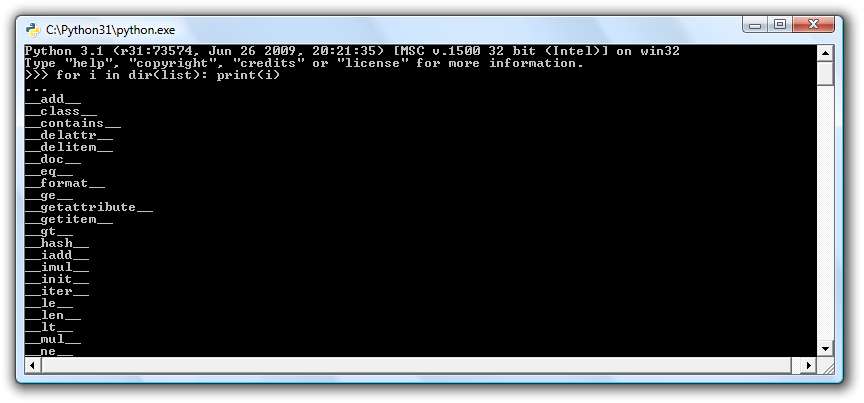

In those cases, you can use an interactive interpreter to help you. If you have Python installed on your system, you have it already. If you are using Windows, this will be the python.exe application in your Python installation directory (C:\Python31\ by default, considering the installation of Python 3.1), as seen in Figure 7.8. In Linux or OSX, you have to type “python” in any console and you are good to go.

You can also use the Blender Python console. Change one of your current windows into the console, and you should see the screen shown in Figure 7.9.

Now you can use it to type simple codes, or to run a help or a dir into any of the Python modules. Unfortunately, only Blender modules have the auto-complete working from there.

Another important strategy is to keep the development of new functionalities outside the main file. For example, if you need to develop a navigation system (as we will soon), you don’t need to use your real big, high-textured scenario. Definitively not for the early tests. If you keep independent systems that work together, you will be able to identify errors faster and easier and even to port fixes over to other projects smoothly.

Designing Your Python Script - Study Example

We are now going to dive into an example of writing and planning a Python script for the game engine from scratch. We will assume that you have already covered all the basics of Python scripting and the general understanding of game engine internals so we can move on to its real usage. More specifically, we are going over the writing process of a camera navigation system for an architectural visualization walkthrough. This study case is actually the system developed for a commercial project for an Italian book project. In general, we needed to implement a system to navigate and interact in a virtual model of an Italian Doric temple. Here, however, we are going to develop it under a sandbox and reapply it into another file, emulating what you could do with your own projects.

Unlike gaming cameras, a virtual walkthrough can use a very simple navigation system compound of (1) an orbit mode to look at the exterior of the building; (2) a walk mode to navigate inside the building with gravity simulation and collision; (3) and a fly mode to freely explore the virtual environment with collision only. The other requirement was to make the system as portable as possible, and with the least amount of logic bricks.

All of those aspects must be considered from the first phases of the coding process. With a well-defined design, you can plan the most efficient system in the short and long run.

Pencil and Paper, Valuable Coding Assets

One of the most remarkable moments during my coding studies was at Blender Conference 2008. I was still in my first steps of learning C++ and OpenGL coding, and I got the chance to explain a game engine bug to Brecht van Lommel[md]a really experienced and acknowledged Blender coder and a very inspiring person. The bug itself was hard to explain through the Internet; it’s the one behind the implementation of canvas coordinates for 2D filters presented in Chapter 5. I was pleased enough to have his input on this, but even more impressive was seeing him code a partial solution right in front of me. At this point, I learned an important lesson. It doesn’t matter how advanced and technical the coding is that you are working on; you can always have a great time sketching your ideas and plans with old-fashioned pencil and paper. This is how he solved the problem, clearly laying down the ideas and organizing them logically. I never forgot that[md]thanks, Brecht!

The system will consist of one camera for the orbit mode, and one to be used for both the fly and walk mode. Each mode works as described in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Comparison of Different Navigation Cameras

| Orbit | Walk | Fly | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical Rotation Angle (Z) | -200º to 200º | Free | Free |

| Horizontal Rotation Angle (X) | 10º to 70º | -15º to 45º | Free |

| Moving Pivot | None | Empty | Empty |

| Horizontal Rotation Pivot | Empty | Empty and Camera | Camera |

| Vertical Rotation Pivot | Empty | Empty | Empty |

- Empty: is an empty object the camera is parented to.

Try It Out

In order to illustrate it better, you can see the working system demonstrated in the book file: \Book\Chapter7\4_navigation_system\camera_navigation.blend. To switch modes press 1, 2, or 3. This will change the mode to orbit, walk, and fly, respectively. To navigate, you can use the mouse and the keys WASD.

3D World Elements

Open up the file \Book\Chapter7\4_navigation_system\camera_navigation.blend.

You will find two cameras and different empty objects in the first layer:

-

scripts - an empty to calls all the scripts.

-

CAM_Move - the camera for the walk and fly mode.

-

CAM_Orbit - the camera for the orbit mode.

-

CAM_back, CAM_front, CAM_side, CAM_top - empties to store the position and orientation for the game cameras.

-

MOVE_PIVOT - the pivot for the walk and fly camera.

-

ORB_PIVOT - the pivot for the orbit camera.

In the second layer, you will find the collision meshes[md]the ground and the vertical elements. Everything is very simple here, since we only need to test the system, and for that a few low poly obstacles work fine.

Understanding the Code

/Book/Chapter7/4_navigation_system/camera_navigation.py

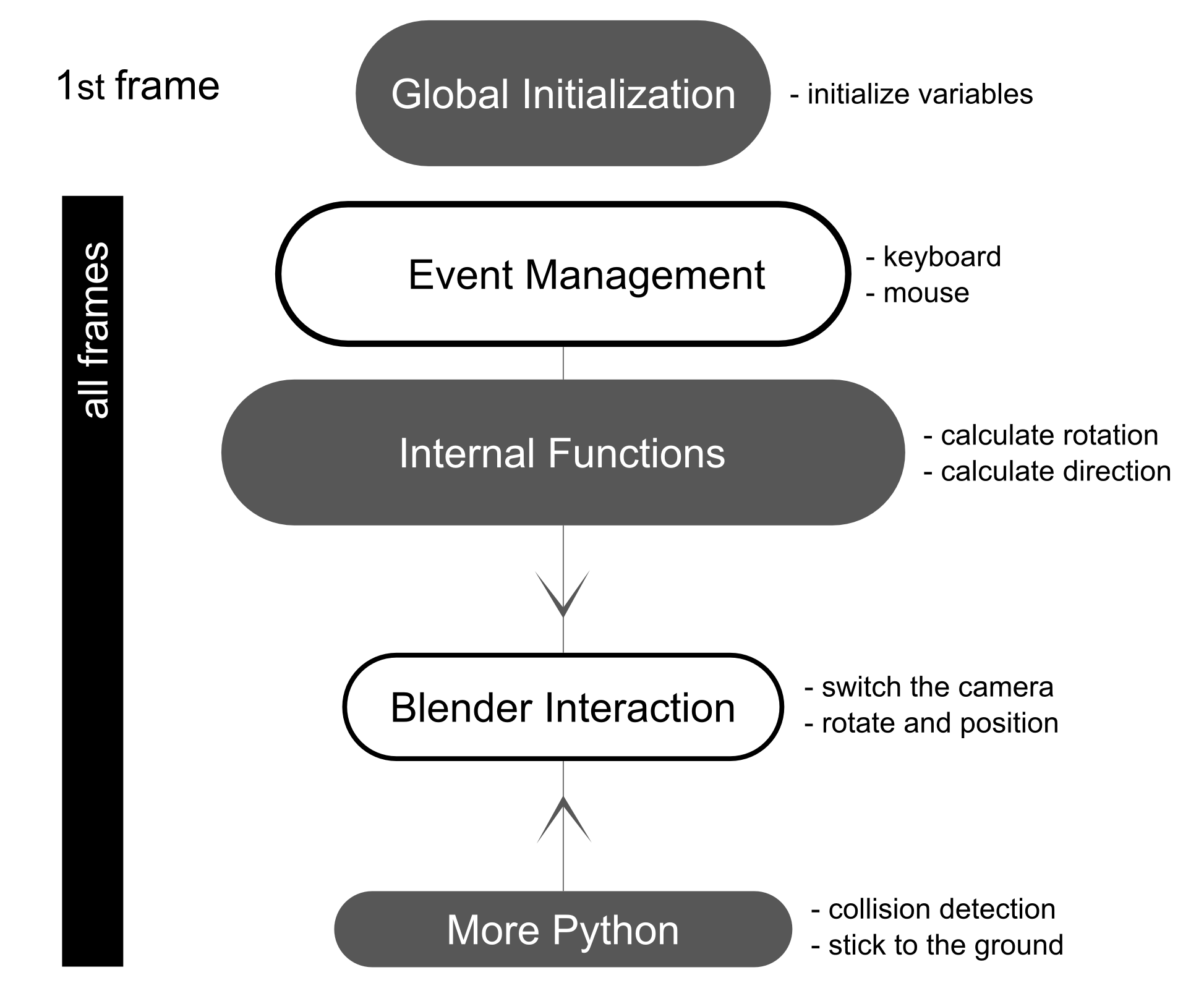

This program is divided into five different parts:

- Global Initialization,

- Event Management,

- Internal Functions,

- Game Interaction,

- More Python.

The diagram in Figure 7.10 illustrates how they relate to one another. Now let’s take an inside look at each of them.

Global Initialization

camera_navigation.init_world()

There is one function that is loaded once at the beginning of the game; we call it “init world”[md]init_world inside scripts.py. We are going to check the priority option in the Python controller to make sure this script runs on top of all the others. In this function, you will first find the global initialization. We are going to store in the global module logic all the elements we are going to reuse over the scripts. That way we don’t need to get the object list every time we need a particular object. A common technique is to store the scene object as well. Therefore, for every scene, you can run a script at the beginning of the game that stores a reference to the current scene globally:

33 G.scenes = {"main":G.getCurrentScene()}

34 objects = G.scenes["main"].objects

Save and Load a game with GlobalDict

Since the module logic is accessible from all the functions and all the scenes, it can be used to store “global” objects. If you need to preserve those objects and variables between game sessions (i.e., after you close your game), you can store them inside the dictionary logic.globalDict and use logic.saveGlobalDict() and logic.loadGlobalDict() to save and load it.

To store the camera information, we are first going to create a global dictionary named cameras. We will use it to store the camera objects, their pivot, and the original orientation of the orbit pivot:

43 G.cameras = {}

44 # orbit camera

45 camera = objects["CAM\_Orbit"]

46 pivot = objects["ORB\_PIVOT"]

47 G.cameras["ORB"] = [camera, {"orientation":pivot.worldOrientation}, pivot]

48 # fly/walk camera

49 camera = objects["CAM\_Move"]

50 pivot = objects["MOVE\_PIVOT"]

52 G.cameras["MOVE"] = [camera, {"orientation":pivot.worldOrientation, "position":pivot.worldPosition}, pivot]

Now that we have our objects instanced, we can set the initial values for our functions, such as the camera rotation restrictions. We don’t want the cameras to look under the ground; thus, we need to manually set our limits. Although we could set those limits directly in the orbit and look functions, having all the parameters in the same part of code is easier to tweak (and slightly faster since they don’t need to be reassigned every frame).

External Settings File

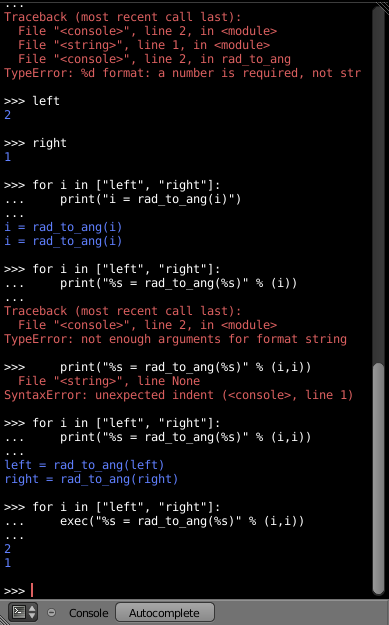

Another common workflow is to have a separate python file (for example, settings.py) with all the variables set. Then in your working script, you simply have to do: import settings.py and use e.g. settings.left.

# Camera Orbit settings:

58 # angle restriction in degrees

59 left = -220.0

60 right = 220.0

61 top = 70.0

62 bottom = 10.0

63

64 # convert all of them to radians

65 left = m.radians(left)

(. . .)

70 # store them globally

71 G.orb_limits = {"left":left, "right":right, "top":top, "bottom":bottom}

72

# Camera Walk/Fly settings:

(. . .)

Last, but not least, we need to create the variables we are going to read and write between the functions. Initializing them here allows us to read them since the first frame of the game. This is especially important for variables that are going to be used in the event management functions - for different values of nav_mode and walk_fly, we are going to run different functions for the camera movement.

103 G.walk_fly = "walk"

104 G.nav_mode = "orbit"

Event Management

camera_navigation.mouse_move

camera_navigation.keyboard

Apart from the Always sensor needed for the camera_navigation.init_world() function, there are two other sensors we need - a keyboard and a mouse sensor. All the interaction you will have with this navigation system will run through those functions.

scripts.mouse_move

Let’s first take a look at the mouse sensor controlling system:

210 def mouse_move(cont):

211 owner = cont.owner

212 sensor = cont.sensors["s\_movement"]

213

214 if sensor.positive:

215 if G.cameras["CAM"] == "ORB":

216 orbit_camera(sensor)

217 else:

218 look_camera(sensor)

It looks quite similar to the script template we saw recently. A difference is that instead of activating an actuator, we are calling a function to rotate the view. Actually, according to the current camera (orbit or fly/walk), we will have to call different functions (orbit_camera and look_camera respectively). Also, you can see that the function gets the controller passed as an argument. The game engine passes the controller by default for the module when using the Python Module controller. The argument declaration in the function is actually optional. So you could replace line 210 of the code with the following two lines, and it would work just as well:

def mouse_move():

cont = G.getCurrentController()

scripts.keyboard

The second event management function handles keyboard inputs. This function takes the sensor input and calls internal functions according to the pressed key. If the pressed key is W, A, S, or D, we move the camera. If the key is 1, 2, or 3, we switch it.

110 def keyboard(cont):

111 owner = cont.owner

112 sensor = cont.sensors["s\_keyboard"]

113

114 if sensor.positive:

115 keylist = sensor.events

117 for key in keylist:

118 value = key[0]

119

120 if G.cameras["CAM"] == "MOVE":

121 if value == GK.WKEY:

122 # Move Forward

123 move_camera(0)

124 elif value == GK.SKEY:

125 # Move Backward

126 move_camera(1)

127 elif value == GK.AKEY:

128 # Move Left

129 move_camera(2)

130 elif value == GK.DKEY:

131 # Move Right

132 move_camera(3)

133

134 # CAMERA SWITCHING

135 if value == GK.ONEKEY:

136 change_view("orbit", "orbit")

137 elif value == GK.TWOKEY:

138 change_view("front")

139 elif value == GK.THREEKEY:

140 change_view("top", "fly")

(...)

For a World with Fewer Logic Bricks

If you don’t want to use a keyboard sensor, you can use an internal instance of the keyboard module. You can read about this in the “bge.logic API” section later in this chapter, or on the online API page: http://www.blender.org/documentation/blender_python_api_2_66_release/bge.logic.html#bge.logic.keyboard.

Internal Functions

scripts.move_camera

scripts.orbit_camera

scripts.look_camera

These three functions are called from the event management functions. In their lines, you can find the math responsible for the camera movement. We’re calling them “internal functions” because they are the bridge between the sensors’ inputs and the outputs in the game engine world.

scripts.move_camera

The function responsible for the camera movement is very simple. In the walk and fly mode, we are going to move the pivot in the desired direction (which is passed as argument). Therefore, we first need to create a vector to this course. If you are unfamiliar with vectorial math, think of vector as the direction between the origin [0, 0, 0] and the vector coordinates [X, Y, Z].

336 def move_camera(direction):

338 if not G.cameras["CAM"] == "MOVE": return

339 MOVE = 0.25 # speed

340

341 if direction == 0: # Forward

342 vector = M.Vector([0, 0, -MOVE])

344 elif direction == 1: # Backward

345 vector = M.Vector([0, 0, MOVE])

347 elif direction == 2: # Left

348 vector = M.Vector([-MOVE,0,0])

350 elif direction == 3: # Right

351 vector = M.Vector([MOVE, 0, 0])

(...)

356 # now that we calculated the vector we can move the pivot

357 # to be continued in the Game Interaction section

Here the vector is the movement we need to apply to the pivot in order to get it moving. The size of the vector (MOVE) will act as intensity or speed of the movement.

scripts.orbit_camera

We decided to use different methods for the walk/fly camera and the orbit one. In the orbit camera, every position on the screen corresponds to an orientation of the camera.

If you want to study this part of the script in particular, you can turn on the Mouse Cursor in the Render Panel. That way, you can see that the same cursor position will (or should) always generate the same view.

224 def orbit_camera(sensor):

228 # Get screen size, attributes from the sensor and global variables

229 screen_width = R.getWindowWidth()

230 screen_height= R.getWindowHeight()

231

232 win_x, win_y = sensor.position

233

234 # G.orb_clamp is in radians

235 orb_limits = G.orb_limits

236 left_limit = orb_limits["left"]

237 right_limit = orb_limits["right"]

238 bottom_limit = orb_limits["bottom"]

239 top_limit = orb_limits["top"]

240

241 # Normalizing x to run from left to right limits

242 x = win_x / screen_width

243 x = left_limit + (x * (right_limit - left_limit))

244

245 # Normalize y to run from top to bottom limits

246 y = win_y / screen_height

247 y = top_limit + (y * (bottom_limit - top_limit))

248

249 # Flip the vertical movement

250 y = m.pi/2 - y

251

254 # Calculate the new orientation matrix

255 mat_ori = G.cameras["ORB"][1]["orientation"]

256

257 mat_x = M.Matrix.Rotation(x, 3, 'Z')

258 mat_y = M.Matrix.Rotation(y, 3, 'X')

259

260 ori = mat_x * mat_y

261

262 # now we can use ori as our new orientation matrix

264 # to be continued in the Game Interaction section

(...)

The first lines that deserve our attention here are the normalizing operation. To normalize a value means to convert it to a range from 0.0 to 1.0. In our case, it can be understood as the mouse pointer coordinates relative to the screen dimensions (width and height):

242 x = win_x / screen_width

Even Fewer Logic Bricks and Normalized Mouse Coordinates

It’s important to always use normalized coordinates for your screen operations. Otherwise, different desktop resolutions will produce different results in a game. As a counter edge case, you may need the absolute coordinates for mouse events if you want to assure minimum clickable areas for your events. You don’t always need to normalize the mouse coordinates manually. Like the keyboard sensor, you can replace the mouse sensor by an internal instance of the mouse module. The coordinates from bge.logic.mouse run from 0.0 to 1.0 and can be read anytime. (You can even link your script to an Always sensor, leaving the Mouse sensor for the times where you are using more logic bricks.) You can read about this in the “bge.logic API” section in this chapter or on the online API page: http://www.blender.org/documentation/blender_python_api_2_66_release/bge.logic.html#bge.logic.keyboard

Now a simple operation to convert the normalized value into a value inside our horizontal angle range (-220º to 220º):

243 x = left_limit + (x * (right_limit - left_limit))

We run the same operation for the vertical coordinate of the mouse. Though you must be aware that the canvas height runs from the top (0) to the bottom (height), this is different from what we could expect (or from OpenGL coordinates, for example). In order to better understand the flipping operation (line 257), you can first comment/uncomment the code to see the difference.

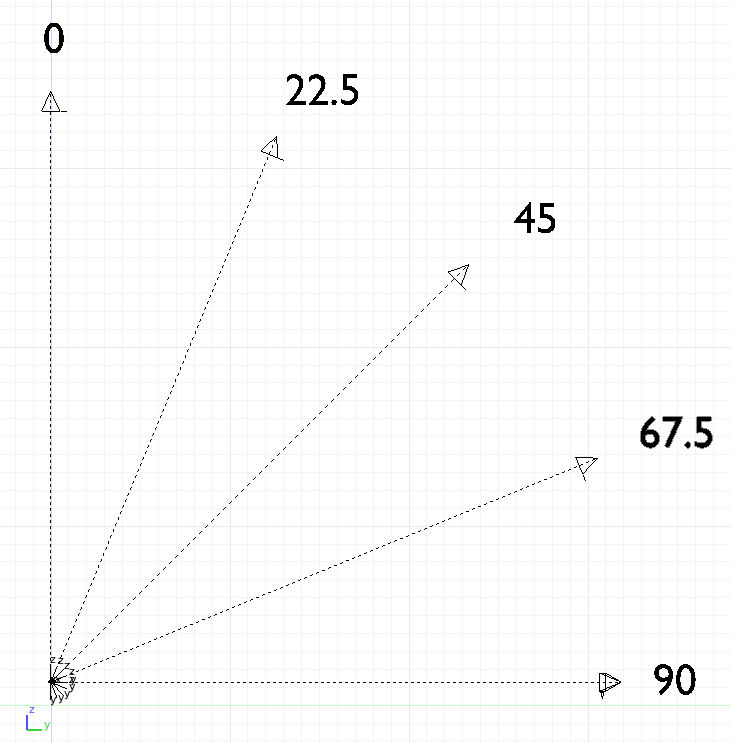

Next find in the .blend file the pivot empty (ORB_PIVOT) and play with its rotation in the X axis. The rotation is demonstrated in Figure 7.11. Therefore, if we subtract our angle from 90º (PI/2 in radians), we get the proper angle to rotate the pivot vertically.

250 y = m.pi/2 – y

scripts.look_camera

The function to rotate the walk/fly camera is quite different from the orbit one. We don’t have a direct relation between mouse coordinate and camera rotation anymore. Here we get the relative position of the cursor (from the center) and later force the mouse to be re-centered[md]to avoid continuous movement unless the mouse is moved again.

In order to get the relative position of the cursor, the normalizing function needs to be different. This time we want the center of the screen to be 0.0 and the extreme edges of the canvas (border of the game window) to be -0.5 and 0.5.

291 x = (win_x / screen_width) - 0.5

292 y = (win_y / screen_height) - 0.5

The values of x and y can be used directly as radians angles to rotate the camera. However, when we are walking, we want to restrict the view vertically. This design decision means that we need to limit the view angle to a maximum and minimum range. Sure, this turns tying your shoes into a circus challenge. Though it may seem like overkill, this limitation helps add a better sense of reality to our navigation system.

The solution is to get the current camera vertical angle and see if by adding the new angle (i.e., vertical mouse move) we would end up over the limit of 45º. If so, we clamp the new angle to respect this value. To get the vertical angle, remember that the camera pivot (an empty object) is always parallel to the ground. Therefore, the vertical angle can be extracted from the camera’s local orientation matrix. If that still doesn’t make sense to you, try to find some 3D math tutorials online).

302 # limit top - bottom angles

303 if G.walk_fly == "walk":

304 angle = camera.localOrientation[2][1]

305 angle = m.asin(angle)

306

307 # if it's too high go down. if it's too low go high

308 if (angle + y) > top_limit: y = top_limit - angle

309 elif (angle + y) < bottom_limit: y = bottom_limit - angle

For the actual project this was originally designed for, we ended up moving the orbit camera code to be a subset of the walk/fly. Having the mouse always centered comes in handy when you have a user interface on top of that, and it needs to alternate between mouse clicking and camera rotating. Although the methods are different, the results are the same.

Game Interaction

camera_navigation.change_view

And the outcome of the functions:

camera_navigation.move_camera

camera_navigation.look_camera

camera_navigation.orbit_camera

In the previous section, we saw how the angles and directions were calculated with Python. However, we deliberately skipped the most important part: applying it to the game engine elements. It includes activating actuators (as we do in the change_view() function) or directly interfering in our game elements (cameras and pivots).

Outcome of the functions: scripts.move_camera, scripts.look_camera, and scripts.orbit_camera

Let’s put the pieces together now. We already know the camera future orientation and position. Therefore, there is almost nothing left to be calculated here. Nevertheless, there are distinct ways to change the object position and orientation.

In move_camera(), we are going to use an instance method of the pivot object called applyMovement (vector, local). This is part of the game engine methods (another one is applyRotation you will see next) we explain later in this chapter in the “Using the Game Engine API” section. This built-in function translates the object using the vector passed as a parameter. It can either be relative to the local or world coordinates:

336 def move_camera(direction):

(. . .)

356 # now that we calculated the vector we can move the pivot

357 pivot = G.cameras["MOVE"][2]

358 pivot.applyMovement(vector, True)

In a similar way in the look_camera() function, we will apply the rotation in the camera object. This has the advantage of sparing the hassles of 3D math, matrixes, and orientations. Also, instead of manually computing the new orientation matrix in Python, we can rely on the game engine C++ native (i.e., fast) implementation for that task.

269 def look_camera(sensor):

(. . .)

314 if G.walk_fly == "walk":

315 # Look Up rotation

316 camera.applyRotation([y,0,0], 1)

317

318 # Look Side rotation

319 pivot.applyRotation([0, -x, 0], 1)

Although we are leaving the math calculation to the game engine, we should still be aware of how it works. The applyRotation() routine works with Euler angles (as a gimbal machine). The effects for the walk and the fly modes are very similar. The only difference is whether the rotation is local or global and the axis to rotate around:

322 else: # G.walk_fly == "fly"

323 # Look Side rotation

324 pivot.applyRotation([0, 0, -x], 0)

325

326 # Look Up rotation

327 pivot.applyRotation([y, 0, 0], 1)

In the orbit_camera() function, we calculated the orientation matrix of the pivot. This matrix is no more than a fancy mathematical way of describing a rotation. Since we already have the matrix, all we need to do is to set it to our pivot orientation.

The orientation is a Python built-in variable that can be read and written directly by our script. We will talk more about this in the “Using the Game Engine API - Application Programming Interface” part of this chapter.

223 def orbit_camera(sensor):

(...)

261 # now we can use ori as our new orientation matrix

262 pivot = G.cameras["ORB"][2]

263 pivot.orientation = ori

scripts.change_view

After the user presses a key (1, 2, or 3) to change the view, we call the change_view() function to switch to the new camera (with a parameter specifying which camera to use). This function consists of two parts: first, we set the correct position and orientation for the camera and pivot; secondly, we change the current camera to the new one.

Decomposing the View Orientation

Keep in mind that the desired orientation (stored in the empty and accessed through the G.views dictionary) represents the new view orientation. In our system, this view orientation is the combination of the parent object (pivot) orientation with the child one (camera).

Let’s start simple and build up as we go. First the orbit camera: in the orbit mode the camera is stationary[md]its position never changes. All we need to do is reset the pivot orientation to its initial values. Its orientation was globally stored back in the init_world() function. So now we can retrieve and apply it to the pivot:

155 dict = G.cameras["ORB"]

157 pivot = dict[2]

158 pivot.orientation = dict[1]["orientation"]

The fly camera is slightly different. In this case, the camera orientation contains no rotation (i.e., an identity matrix). Therefore, it’s up to the pivot orientation to match the view orientation. In other words, the pivot orientation matrix is exactly the same as the view orientation matrix:

169 pivot.position = G.views[view].position

170 pivot.orientation = G.views[view].orientation

171 camera.orientation = [[1,0,0],[0,1,0],[0,0,1]]

177 if G.walk_fly == "walk":

178 fly_to_walk()

For the walk camera, we have yet another situation. The mode we are coming from (fly) has the camera pivot orientation (same as camera.worldOrientation) as the current view orientation. However, for the walk mode, the pivot needs to be parallel to the ground.

For that, we need to rotate it a few degrees to align with the horizon. The camera now will be looking to a different point (above/below the original direction). In order to realign the camera with the view orientation, we need to rotate the camera in the opposite direction. This way, the pivot and camera rotations void each other (with the benefit of having the pivot now properly aligned with the ground).

190 def fly_to_walk():

(...)

194 view_orientation = camera.worldOrientation

195 euler = view_orientation.to_euler()

196 angle = euler[0] - (m.pi/2)

197

198 pivot.applyRotation([-angle,0,0],1)

199 camera.applyRotation([angle,0,0],1)

Reasoning Behind the Design

There is another reason for keeping this as a separate function. Originally, I was planning to switch modes (walk/fly) while keeping the same camera position and view. Although I dropped the idea, I decided to keep the system flexible in case of any turn of events (clients[md]who understands their minds?).

Now that the new camera and pivot have the correct position and orientation, we can effectively switch cameras. For that, we first set the new camera in the Scene Set Camera actuator. Next, we activate the actuator and the camera will change:

181 act_camera.camera = dict[0]

182 cont.activate(act_camera)

More Python

scripts.collision_check

scripts.stick_to_ground

The script system shown so far handles all the interaction from the game engine sensors to the 3D world elements. Even though this covers most parts of a typical script architecture, I’d be lying if I said this is all you will be doing in your projects. Very often, you will need a script called once in a while that deals directly with the game engine data. In our case, we will have two “PySensors” to control the collision and to stick our camera to the ground while walking.

We could have them both working attached to an Always sensor. However, this would not be too efficient. Since we only need them while walking and flying, they can be integrated with the Keyboard sensor pipeline. The stick_to_ground() function will be called after any key is pressed if the current mode is “walk”:

142 if G.nav_mode == "walk" and G.walk_fly == "walk":

143 stick_to_ground()

The collision system can be used even more specifically. Inside the move_camera() function, we will use the collision test to validate or discard our moving vector:

353 # if there is any obstacle reset the vector

354 vector = collision_check(vector, direction)

If the collision_check() test finds any obstacle in front of the camera, it returns a null vector ([0, 0, 0]). Otherwise, it leaves the vector as it was set, which will then move the camera.

The code of those functions is very particular to this project; therefore, we’re not going into more detail here. (You are encouraged to take a look at the complete code in the book file, though). Nevertheless, the key point is to understand the role of those functions in the script architecture. Those scripts can complement the functionality of other functions, to rule your game in a global and direct way, or simply to tie things together.

Reusing Your Script

One of the reasons this system was designed so carefully is because of the need for portability. You don’t want to rewrite a navigation system every time you have a new project. This is not particular to this script example. Very often, you will be recycling your own scripts to adapt them to new files. Let’s go over some principles you should know.

File Organization - Groups and Layers

The first thing to have in mind is how your final file will look. Do you want the script system to be merged with the rest of the existent Blender file? Do you want to keep them in separated scenes (very common for user interfaces)? Will you need to access/edit the script system elements later?

In our case, there is no need for an extra scene. However, we need to make sure that the navigation system elements are easy to access (especially the empties with the cameras’ positions). If you can afford to dedicate one layer exclusively to the navigation system elements, do it. Make sure that the desired layer is empty in the model file and that all the objects you want to import are contained in this layer.

If it’s not possible to have all your elements in a single layer, you can create a group for them. That way, you can always quickly isolate them to be listed in the outliner and selected individually. The other advantage of using groups is during importing. It’s easier to select a group to be imported than to go over all the individual objects, determining which one should be imported and which one is part of the test environment (which usually doesn’t have to be imported).

Tweaks and Adjustments - Getting Your Hands Dirty

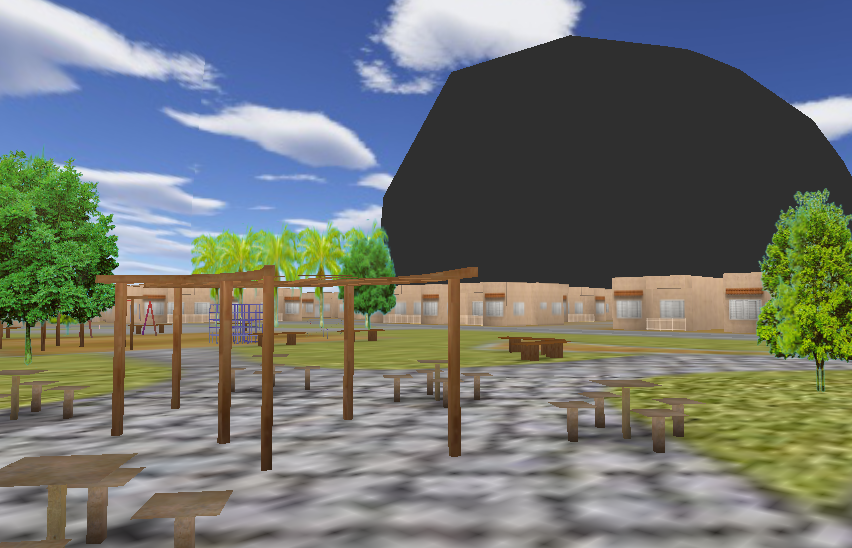

Open the file /Book/Chapter7/4_navigation_system/walkthrough_1_base/walkthrough.blend

This small file is part of the presentation of an architectural walkthrough of an urban project (see Figure 7.12) that I (Dalai) did. It’s an academic project and only my second project using the game engine. As you can see, there are absolutely no scripts in it[md]all the interaction is done with logic bricks. I didn’t use Python for this project mainly because I had absolutely no knowledge of Python at all back then (and the project was done in six days).

It’s time for redemption. Let’s replace its navigation system with the Python system we just studied. For convenience, this file was already organized to receive the navigation elements (cameras, empties, and so on.).

Organize and Append Your File

In this case, we decided to group all the navigation elements in a group called NAVIGATIONSYSTEM and to make sure they are all in layer 1. You can use the Outliner to make sure you didn’t miss any object out of the group. Leave the lamps and the collision objects out of the group.

To see a snapshot of the file at this moment, you can find it in the book files at: /Book/Chapter7/4_navigation_system/walkthrough_2_partial/camera_navigation.blend

Now open the walkthrough file again and append the NAVIGATIONSYSTEMwe created. It’s important not to link the group but to append it. Linked elements can only be moved in their original files; thus, you should avoid them in this case.

-

Open the Append Objects Dialog (Shift+F1).

-

Find the NAVIGATIONSYSTEM group inside the camera_navigation file.

-

Make sure the option “Instance Groups” is not checked. (This would insert the group, not the individual elements.)

-

Click on the “Link/Append from Library.” (This will add the group.)

-

Set CAM_Orbit as the default camera. (Tip: Use the Outliner to find the object; it’s inside the ORB_PIVOT.)

A snapshot with those changes can be found at:

/Book/Chapter7/4_navigation_system/walkthrough_2_partial/walkthrough.blend

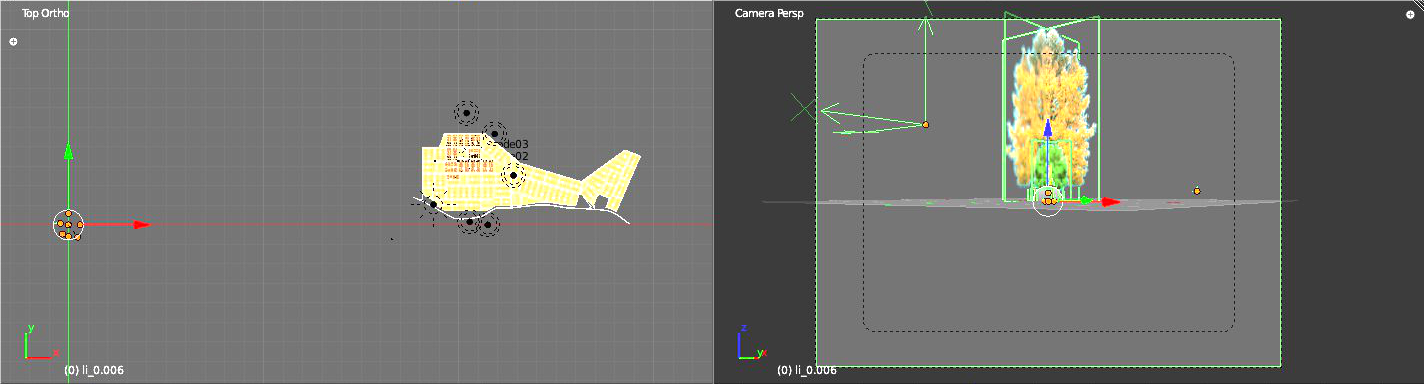

Now if you run the application, the navigation system should work - kind of (see Figure 7.13).

Adjustments in Loco

As you can see in Figure 7.13, the new camera system looks absurdly wrong. There are two main reasons for that: the walkthrough file elements are far away from the file origin [0, 0, 0], and the cameras are not prepared for a project with this magnitude (their clipping parameters are way too low). We will need to move the objects to their new correct places, adjust the camera parameters, and do a small intervention in the script file:

All the elements from NAVIGATIONSYSTEM group (layer 1):

Move them 2000 in X and 350 in Y.

Empties :

-

CAM_front and CAM_back - Those empties will hold the position for walk cameras. Make sure their position from the ground is at the human eyes (~1.68).

-

CAM_top and CAM_side - Those empties will be used in Fly Mode. Here, we should also make sure their initial orientation looks good. The easiest way to do that is by using the Fly Mode (select the object, set it as current camera, and use Shift+F).

The one thing missing for the camera is to increase the clipping distance. That way, we can see all the skydome around the camera (see before and after in Figure 7.14).

Cameras :

-

CAM_Orbit - Adjust initial Z, change clip ending to 1000.

-

CAM_Move - change clip ending to 1000.

A snapshot with those changes can be found at:

/Book/Chapter7/4_navigation_system/walkthrough_3_partial/walkthrough.blend

| Camera clipping of 400 | Camera clipping of 1000 |

|---|---|

|

|

Make Sure That Collision Is Set Properly

All the houses, the ground, and the other 3D objects already have collision enabled in this file. In other situations, however, you may need to change the collision objects, enabling or disabling their collisions accordingly. The Python raycast uses the internal Bullet Physics engine under the hood. In order to prevent the camera from going through the walls and the ground, set enough collision surfaces (but not too much, so that you don’t compromise the performance of your game).

Script Tweaks

Finally, it’s good to fiddle a bit with the script. Due to the particularities of this project (mainly its scale), you may feel that everything happens a bit too fast. It’s up to you to change the settings in the init_world function. Also, it would be interesting to explore multiple viewpoints for this presentation. We have already positioned the side and back empties. Although we were not using them previously, their names are present in the script as part of the available cameras list:

93 available_cameras = ["front", "back", "side", "top"]

The difference now is that we will make the camera actually change to the side and back views when you press the keys four and five respectively. As you can see here, it’s really easy to expand a system like this. Try to create a fifth camera (add a new empty) and see how it goes. To enable the “side” and “back” cameras, the only code we have to add is:

110 def keyboard(cont):

(. . .)

new elif value == GK.FOURKEY:

new change_view("side")

new elif value == GK.FIVEKEY:

new change_view("back", "fly")

There is not much more to be done here. This is a simple script, but its structure and the workflow we presented are not much different from what you will find in more complex systems you may have to implement or work with. There are different ways to implement a navigation system. This one was designed focusing on a didactic structure (clean code as opposed to a highly optimized system that is hard to read) and robustness (easy to expand). Try to find other examples or, better yet, build one yourself.

The final file is on the book files as:

/Book/Chapter7/4_navigation_system/walkthrough_4_final/walkthrough.blend.

Using the Game Engine API - Application Programming Interface

The game engine API is a bridge connecting your Python scripts with your game data. Through those modules, methods, and variables you can interact with your existent logic bricks, game objects, and general game functions.

The official documentation can be found online in the Blender Foundation website:

http://www.blender.org/documentation/blender_python_api_2_66_release

We will now walk through the highlights of the modules. After you are familiar with their main functionality, you should feel comfortable to navigate the documentation and find other resources.

Game Engine Internal Modules

-

Game Logic (bge.logic)

-

Game Types (bge.types)

-

Rasterizer (bge.render)

-

Game Keys (bge.events)

-

Video Texture (bge.texture)

-

Physics Constraints (bge.constraints)

-

Application Data (bge.app) //TODO

Stand-Alone Modules

-

Audio System (aud)

-

Math Types and Utilities (mathutils)

-

OpenGL Wrapper (bgl)

-

Font Drawing (blf)

bge.logic

The main module is a mix of utility functions, global game settings, and logic bricks replacements. Some of those functions were already covered in the tutorial, but they are here again for convenience sake. We will look at some of the highlights.

getCurrentController()

Returns the current controller. This is used to get a list of sensors and actuators (to check status and deactivate respectively), and the object the controller belongs to:

controller = bge.logic.getCurrentController()

object = controller.owner

sensor = controller.sensors['mysensor']

If you are using Python modules instead of Python scripts directly (see Python Controller), the controller is passed as an argument for the function:

def moduleFunction(cont):

object = cont.owner

sensor = cont.sensors['mysensor']

getCurrentScene()

This function returns the current scene the script was called from. The most common usage is to give you a list of all the game objects:

for object in bge.logic.getCurrentScene().objects: print(object)

expandPath()

If you need to access an external file (image, video, Blender, etc.), you need to first get its absolute path in the computer. Use single backslash (/) to separate folders and double backslash (//) if you need to refer to the current folder:

video_absolute_path = bge.logic.expandPath('//videos/video01.ogg')

sendMessage(), addScene(), start/restart/endGame(),

These functions copy the functionality of existent actuators. They are Python replacement for those global events when you need a direct way to call them, bypassing the logic bricks.

LibLoad(), LibNew(), LibFree(), LibList()

There are cases when you need to load the content of an external Blender file at runtime. This is known as dynamic loading. The game engine supports dynamic loading of actions, meshes, or complete scenes. The new data blocks are merged into the current scene and behave just like internal objects:

bge.logic.LibLoad("//entities.blend", "Scene")

Beware of Lamps

New Lamp objects can be dynamically loaded from external files. However, in GLSL mode, they will not work as a light source for the material shaders, since the shaders would need to be recompiled for that.

globalDict, loadGlobalDict(), saveGlobalDict()

The bge.logic.globalDict is a Python dictionary that is alive during the whole game. It’s a game place to store data if you need to restart the game or load a new file (level) and need to save some properties. In fact, you can even save the globalDict with the Blender file during the game and reload later.

bge.logic.globalDict["password"] = "kidding, kids never save your passwords in files!"

bge.logic.saveGlobalDict() # save globalDict externally

bge.logic.loadGlobalDict() # replace the current globalDict with the saved one

keyboard

You can handle all the keyboard inputs directly from a script. The usage and syntax are very similar to the Keyboard sensor. You need a script running every logic tic (Always sensor pulsing with a frequency of 0 or every time a key is pressed; Keyboard sensor with “All Keys” set) where you can read the status of all the keys in the bge.logic.keyboard. events dictionary. If instead of inquiry for the status of a particular key (e.g., if spacebar is pressed), you want to list all the pressed keys, you can use the dictionary bge.logic.keyboard.active_events.

The keys for both event dictionaries are the same you use with the Keyboard sensor (see the bge.events module). The status of each key (whether it was pressed, released, kept pressed, or nothing) is the value stored in the dictionary. The keys values are defined in the bge.logic module itself:

keyboard = bge.logic.keyboard

space_status = keyboard.events [bge.events.SPACEKEY]

if space_status == bge.logic.KX_INPUT_JUST_ACTIVATED:

print("space key was just pressed.")

elif space_status == bge.logic.KX_INPUT_ACTIVE:

print("space key is still pressed.")

elif space_status == bge.logic.KX_INPUT_JUST_RELEASED:

print("space key was just released.")

else: # bge.logic.KX_INPUT_NONE

pass

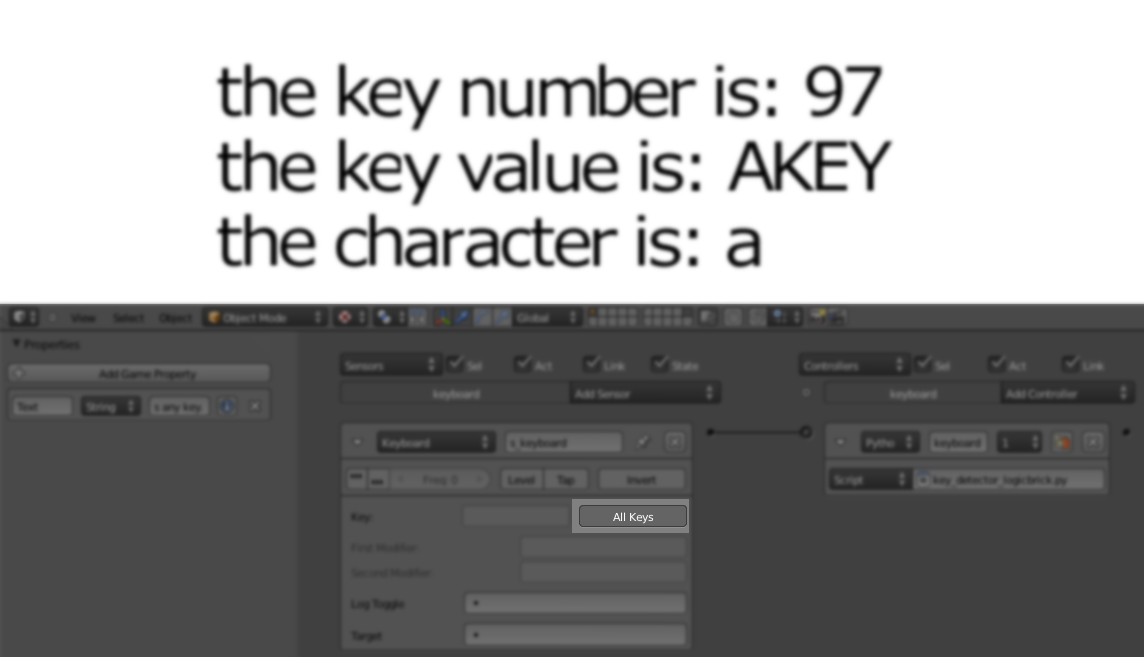

A sample file can be seen at \Book\Chapter7\5_game_keys\key_detector_python.blend . This shows the more Python-centric way of handling keyboard. For the classic method of using a Keyboard sensor, look further in this chapter into the “bge.events” section.

mouse

Similar to the keyboard, this Python object can work as a replacement for the Mouse sensor. There are a few differences that make it even more appealing for scripting[md]in particular, the fact that the mouse coordinates are already normalized. As we explained in the tutorial, this helps you get consistent results, regardless of the desktop resolution. The available attributes are:

-

events: A dictionary with all the events of the mouse (left-click, wheel up, and so on) and their status (for example, bge.logic.KX_INPUT_JUST_ACTIVED).

-

position : Normalized position of the mouse cursor in the screen (from [0,0] to [1,1]).

-

visible : Dhow/hide the mouse cursor (can also be set in the Render panel for the initial state).

joysticks

This is a list of all the joysticks your computer supports. That means the list is mainly populated by None objects, and a few, if any, joystick Python objects. To print the index, name, number of axis, and active buttons of the connected joysticks, you can do:

for i in bge.logic.joysticks:

joystick = bge.logic.joysticks[i]

if joystick and joystick.connected:

print(i, joystick.name, joystick.numAxis, joystick.activeButtons)

For the complete list of all the parameters supported by the Joystick python object, visit the official API: http://www.blender.org/documentation/blender_python_api_2_66_release/bge.types.SCA_JoystickSensor.html

A sample file can be found on \Book\Chapter7\joystick.blend.

Others

There are even more functions available in this module (setMist, getLogicTicRate, and setGravity, for example). Make sure that you visit the online documentation (or the documentation included on the book files) to see them all.

bge.types

Objects, meshes, logic bricks, and even shaders are all different game types. Every time you call an internal function from one of them, you are accessing one of those functions. This happens when you get a position of an object, change an actuator value, and so on.